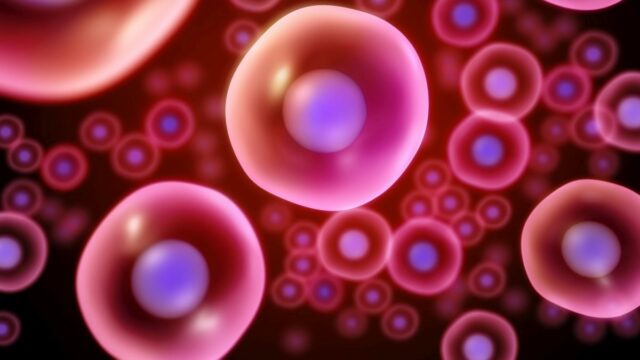

Humans consume more than 74,000 microplastic particles each year, according to a study published this week, but the impact on our health is still unclear.

This shocking article could be used alongside Biological, Chemical and Earth and Space sciences for years 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9.

Word Count: 749

Microplastics are tiny particles of plastic under five millimetres in diameter, which is smaller than the size of a sesame seed.

They usually come from plastic that has degraded, such as shedding from water bottles, plastic packaging and synthetic clothes.

Researchers reviewed 26 previous studies that analysed the amount of microplastic found in fish, shellfish, added sugars, salts, alcohol, tap or bottled water and air, then estimated average consumption based on recommended American dietary guidelines.

Microplastics are present in our food chain

They estimate people eat and inhale between 74,000 and 120,000 particles each year, depending on age and sex, and people who drink only bottled water could consume an additional 90,000 microplastics per year compared to those who drink only tap water.

In an Expert Reaction to the AusSMC, Anas Ghadouani, head of Aquatic Ecology and Ecosystem Studies at the University of Western Australia said it shouldn’t come as a surprise that humans are taking in microplastics since they’ve already been shown to be present in our food chain.

“The irony is that we have been saying that microplastics are everywhere in the environment, and in the scientist mind, humans are part of the environment. So we meant humans as well,” he says.

“But it seems that there is some perceived separation between the environment and humans.”

The amount we consume can’t be measured exactly

So while there is no doubt we are consuming microplastic, the authors acknowledge the amount we could be ingesting is highly variable.

Kevin Thomas, Director of the Queensland Alliance for Environmental Health Sciences told the AusSMC the estimated 74,000 to 120,000 bracket is huge because our current measurement technologies need improving.

“The authors rightly point out the large amount of variation in their estimates, and make known current limitations in the methods used to quantify plastic exposure in consumed items,” he says.

To figure out a more exact measurement, Thomas says we need measurement techniques that can more accurately count such tiny, tiny plastic particles.

But the paper authors say these numbers are likely underestimated, as the figures only account for around 15 per cent of Americans’ caloric intake and ignored food groups like meat, grains and vegetables due to lack of data.

So what does this mean for our health?

Currently, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that the microplastics are having a negative impact on our health, but as Lauren Roman from CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere said, this doesn’t mean there are no negative health effects.

“It’s possible there are and they just haven’t been found, but imminent danger is very unlikely,” she says.

While the current health effects are unclear, the study authors agree there is potential for many complications, as the tiny particles could travel into our tissues, trigger an immune response or carry chemicals and pollutants that were present during the production of the plastics.

Risk of exposure to chemicals through microplastic ingestion

Macquarie University’s Paul Harvey highlights the last point as the issue of most concern.

“Ingesting microplastics may be placing humans at risk of exposure to the various chemicals found within the plastic compounds,” he says.

“This is particularly problematic and concerning for those who are more sensitive to environmental toxins including children and pregnant mothers.”

On an individual scale, while researchers work to figure out exactly how much we’re ingesting and what these microplastics are doing to us, the study authors say the best way to control our microplastic intake is by limiting the amount of bottled water we drink.

On a larger scale, study author Kieran Cox says we need to take a good, hard look at how much we rely on plastic packaging.

“Human reliance on plastic packaging and food processing methods for major food groups such as meats, fruits and veggies is a growing problem. Our research suggests microplastics will continue to be found in the majority—if not all—of items intended for human consumption,” he said.

“We need to reassess our reliance on synthetic materials and alter how we manage them to change our relationship with plastics.”

Ghadouani says the key question researchers must ask now is: “What happens next?”

“What are the physical impact of particles travelling inside the bloodstream? Where is the next stop? Human brain? Many questions for the scientist to try to answer in a short period of time because this is urgent,” he says.

“Now with this evidence, it may start being too close for comfort and hopefully we could see some real action.”

You can read the full AusSMC Expert Reaction here.

Login or Sign up for FREE to download a copy of the full teacher resource